This sermon series is inspired by NPR’s serialized podcast White Lies. You can also find an audiovisual narrative and other materials on the special White Lies website.

Sermon

Three white Unitarian ministers eat dinner at a black café.

It was 1965 in segregated Selma, AL. After dinner, they make long-distance calls at the payphone to check in with their families. Just as the streetlights are coming on, they emerge from the café into the approaching darkness. These men were not from this town.

But what would happen next as they made their way to a meeting – crossing inadvertently in front of a white café – would change the course of their lives, and the course of our nation’s history.

These white Unitarian ministers were in Selma because they had responded to a call from Martin Luther King Jr for clergy across the nation to come demonstrate with African Americans for voting rights.

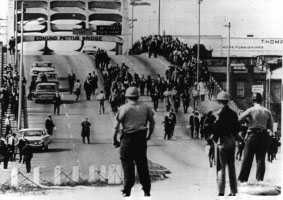

Just two days before they emerged from that café, demonstrators had been savagely beaten by police on the Edmund Pettus bridge in Selma.

The day would be known as Bloody Sunday. The world witnessed the brutality on their TV screens.

These are black and white images but remember these events happened within the lifetimes of many people in this room.

…

Let me pause for a warning – this sermon contains some graphic content, in particular within the next few minutes.

As Cornel West told Unitarian Universalists in his Ware lecture at our 2015 General Assembly:

The condition of truth is always to allow suffering to speak.

-Cornel West

In our country we haven’t scratched the surface of telling these stories about our brutal past – our national sins of slavery, lynching, segregation, hate….

We must allow suffering to speak.

But for black folks, these stories are in your family tree, in your bones, in your present…and so for those for whom these stories are not an education but a re-traumatization – or for children – please do what you need to do and leave the room if needed.

Less than two weeks before Bloody Sunday, Jimmie Lee Jackson was murdered by an Alabama state trooper. Jackson was unarmed and participating in a peaceful march in his city, when the police began beating the marchers. Jackson fled with his family to take refuge in a café. The troopers followed the family and began to beat Jackson’s 82-year old grandfather. Jackson’s mother tried to stop them and was beaten. Jackson intervened, was thrown against a wall, where a trooper put a gun to his side and shot twice. Jackson stumbled out of the café, back through the line of police who continued to beat him as he lurched past. By the time he got to the clinic, the hole in his side was the size of a grapefruit, intestines coming out.

He died 8 days later.

Jimmie Lee Jackson’s gravestone says “He was killed for man’s freedom.”

In his gravestone multiple shotgun holes have appeared.

There’s a memorial to him in the place he was shot, and on it, it says he “gave his life in the struggle for the right to vote.”

The right to vote!

He had tried four times to register to vote.

Joanne Bland, Co-founder of the National Voting Rights Museum, who was 11 years old standing on that bridge on Bloody Sunday, hearing the sounds of her neighbor’s heads being dashed to the ground by police and horses,…she says he didn’t give his life – it was taken from him.

But just two years before Jackson was murdered, civil rights workers never would have imagined that Alabamans would put their lives at risk for the cause.

Two years before, Bernard Lafayette was a young organizer just beginning his work with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee – SNCC. At the SNCC headquarters in Atlanta, Lafayette saw a map of the South and there was Alabama with an X through it.

He asked “Why not Alabama?” They said that they’d already tried there but nothing could be done: in Alabama, they said, “white folks were too mean and black people too scared.”

Lafayette went to Alabama anyway. He later said,

As long as you have people who are afraid, they also believe that nothing can be done. … Black families had worked for the same white family for generations. And some of the women there were wet nurses; they nursed some of the white children. So there was a closeness that you couldn’t imagine. First of all, they didn’t believe change was possible, and then they didn’t want to disturb their relationship because they felt very protective. They used to tell me that if God wanted us to be equal with whites, he would have made us white. You had to have a great imagination that any change was going to happen in Selma, Alabama.

– Bernard Lafayette, SNCC organizer

Change did come.

But sometimes when we look back on the civil rights movement, we forget how much work, how much collaboration, how much strategy, how many failures, how much death, how much active hope it took to make change happen.

They found a way out of no way.

Bill Sinkford, the first black President of our Unitarian Universalist Association, says “There is a belief in the African-American tradition, a statement of faith that says we can find “a way out of no way.”

That was Selma, Alabama – the black X on the map.

Charles Mauldin was 15 when Bernard Lafayette started showing up on the block asking him and his friends simple questions like “why can’t you drink out of the white water fountain?” Beginning to face those questions was terrifying for them because it meant confronting white society.

But Mauldin says:

Once our consciousness was opened… our minds grew by leaps and bounds. And unless you’re sort of booted out of normalcy, then it’s normal to not strive to increase your consciousness.. And Dr. King talked about that .. about ending certain types of normalcies. You know, the normalcy of white supremacy, the normalcy of poverty, the normalcy of the lack of distribution of wealth – that’s normal. It takes electricity to somehow shock you out of that.

Charles Mauldin

For white America, the electric shock that finally led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act – was not Jimmie Lee Jackson’s death, was not even Bloody Sunday, or the countless other well-documented acts of slavery and lynching and brutality against black people.

The electric shock was the murder of a white Unitarian minister.

….

When those three white Unitarian ministers left that café that night, they were walking to a meeting with Dr. King and the movement. They never made it there. They were attacked by 4 or 5 white men who recognized them as those out-of-town white civil rights workers.

Rev. James Reeb was hit in the head. They couldn’t take him to a white hospital because they knew he wouldn’t be treated there. At the black clinic, it was determined he needed a neurosurgeon for a skull fracture and brain bleeding. The other two white ministers accompanied him on a harrowing ambulance ride to Birmingham. He never recovered. His youngest child was 5 years old.

President Johnson and Lady Bird sent yellow roses to the hospital. And after Reeb died, the president sent a government airplane to take the family back to Boston.

Five months later, LBJ passed the Voting Rights Act, referencing James Reeb’s murder in his speech…but not Jimmie Lee Jacksons.

The state trooper who murdered Jimmie Lee Jackson was finally charged in 2007 – 42 years after the crime – and served five months in jail.

And the men who murdered James Reeb were never held to account. Three men were found not guilty by an all-white, all-male jury.

Recently two white journalists from Alabama working for NPR took it upon themselves to inviestigate Reeb’s murder. They found the truth buried in lies – White Lies – that’s the title of their 7-episode series, which is a mix of suspenseful true crime reporting and a deep dive into themes of guilt, memory, truth, and integrity. Next Sunday we’ll be discussing this series together. I strongly encourage you to listen to the podcast – it’s free, riveting, painful, and deeply important.

In these journalists’ reporting they talk to a white woman who was a teenager living in Selma at the time – on her 16th birthday, her father was with a posse of men standing with the sheriff on the Edmund Pettus bridge waiting to attack the marchers. About the jury’s not-guilty verdict, she says:

“I mean, that jury knew the verdict before they went in there. … This was the rules back in the ’60s. You just don’t convict a white man for this civil rights stuff. You just don’t do it. That’s what they had to do.”

One of the journalists, Andrew Beck Grace says:

“That’s what they had to do.” …This is such a common refrain in this story. Hell, in the entire history of our country, this is a common refrain. The people of the past were governed by rules different than the ones we live by now, and so it’s not fair to judge them. Their choices were inevitable. “They had to do it…” …. But what does it mean to treat the people of the past like this, like they had no free will, no choices? When we say the past is off limits for our judgment, we’re not just saying leave it alone. We’re convincing ourselves that our past has nothing to do with our present.”

Andrew Beck Grace

Where our history books don’t blatantly lie about slavery and segregation, they still don’t usually do much to help us reckon with our past.

And a people that doesn’t reckon with our past is bound to repeat it. That’s the cliché, right? That we will repeat the past…?

But the truth is actually more damning than that – We’re not at risk of repeating the past because the past is still here…it’s still happening.

At this point, we took a break in the sermon to listen to an excerpt of the podcast… the last few minutes of Episode 7 in which Joanne Bland talked about getting to the tree’s roots, and Chip Brantley and Andrew Beck Grace also give reflections on the presence of the past in our present.

Tomorrow is Martin Luther King Day. It can be easy to take the feel-good stuff from his speeches – “I have a Dream” …“love is the answer” and forget that King was a radical organizer, surrounded by radical organizers. King was continually investigated by the FBI and scorned even by the left, in the last years of his life because they thought him too radical.

Well-meaning white people would say, “Well I like your goals, but I don’t like your methods.” Or “Too much, too fast.” or “Too divisive.”

And now people say the phrase “Black Lives Matter” is divisive – or that talking about race at all is divisive!

It’s clear that all Lives don’t Matter to our country when we look at the truth – it’s easy to find if you look – the truth about how our country continues to treat black and indigenous and Latinx people.

When James Reeb died, Dr. King eulogized him, having just eulogized Jimmie Lee Jackson in the same chapel just over a week before. I’ll read a portion of his eulogy at length.

Naturally, we are compelled to ask the question, Who killed James Reeb? The answer is simple and rather limited when we think of the who… It is the question, What killed James Reeb? When we move from the who to the what, the blame is wide and the responsibility grows.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

We may say “well it was racists…it was white supremacists”…but King continued:

James Reeb was murdered by the indifference of every minister of the gospel who has remained silent behind the safe security of stained glass windows. He was murdered by the irrelevancy of a church that will stand amid social evil and serve as a taillight rather than a headlight, an echo rather than a voice. He was murdered by the irresponsibility of every politician who has moved down the path of demagoguery, who has fed his constituents the stale bread of hatred and the spoiled meat of racism. … He was murdered by the timidity of a federal government that can spend millions of dollars a day to keep troops in South Vietnam, yet cannot protect the lives of its own citizens seeking constitutional rights. Yes, he was even murdered by the cowardice of every [person]..who stands on the sidelines in the midst of a mighty struggle for justice. …We must be concerned not merely about who murdered [Reeb] but about the system, the way of life, the philosophy which produced the murder.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

White Lies. One of the lies that still thrives in Selma when you talk with people there about Reeb’s death is the lie of white supremacy.

But this lie doesn’t just thrive in deep Alabama, in white supremacists. It thrives in all of us.

White people are not bad. But whiteness – which people actually invented – and the belief that whiteness is supreme, causes separation and suffering for all of us.

White supremacy is the water we swim in.

Cornel West talked about this when he was our Ware lecturer at our 2015 General Assembly, he said,

I’ve got a lot of vanilla brothers and sisters that walk with me and say, Brother West, Brother West. you know, I’m not a racist any longer. Grandma’s got work to do, but I’ve transcended that. And I say to them, I’m Jesus-loving, free, black man, and I’ve tried to be so for 55 years, and I’m 62 now, and when I look in the depths of my soul I see white supremacy because I grew up in America. And if there’s white supremacy in me, my hunch is you’ve got some work to do too.

– Cornel West

Hearing hard truths is part of what it means to be a people of integrity – a people, a faith, who can face the unvarnished truth and let it guide us… a people, a faith, who can let suffering speak and not put up our defenses, not turn away, but instead lament that pain, feel the love in our lament, and then answer the call with courage and tenacity.

—

One of the NPR journalists says towards the end of the series:

The question is, once you’ve called a lie a lie, what does it mean to live with the truth?

So next week will be part 2 of this sermon topic. We’ll look more into who James Reeb was before he was killed. And we’ll talk about ways we can live with the truth and unlearn white supremacy.

I’ll end with some of Rev. Dr. King’s words he spoke to us – UUs – when he was our Ware lecturer at our 1966 General Assembly. This was just before the Left started to abandon him, and just before our own Black Empowerment Controversy.

“There are those wonderful moments in life when you speak before a group that is so near and dear to you that you don’t feel like you have to engage in the art of persuasion. …You know that you are with friends. I can assure you that I feel that way tonight.”

And yet, all the same, he titled his talk: “Don’t sleep through the revolution.”

He ended on the same hopeful note I’ll end on, by using his words from that day, including his quote of one of our own abolitionist ministers, Theodore Parker:

We can sing We Shall Overcome, because somehow we know the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice. We shall overcome because …—”no lie can live forever.” We shall overcome because …—”truth crushed, will rise again.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

May it be so. And may we work to make it so.

– Rev. Emily Wright-Magoon

For further reading/listening:

- White Lies podcast series, including the “bonus” episode they link to from the CodeSwitch podcast.

- We used this meditation God Gave Me a Word by Amy Petrie Shaw in this service.

- 1966 WARE LECTURE: DON’T SLEEP THROUGH THE REVOLUTION, BY DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. UUA GENERAL ASSEMBLY 1966

- WARE LECTURE BY CORNEL WEST, UUA GENERAL ASSEMBLY 2015

- Call to Selma: Eighteen Days of Witness. Richard D. Leonard. Skinner House, 2001. (UUA Bookstore)

- Martin Luther King Jr.’s previously unpublished eulogy for James Reeb (May/June 2001; PDF)

- Listen to Martin Luther King Jr.’s eulogy for James Reeb. Recorded in Selma, Alabama, by Carl Benkert on March 15, 1965.

- The Selma Awakening: How the Civil Rights Movement Tested and Changed Unitarian Universalism (Skinner House Books, 2014).